The Bombai mithai-wala and others are all part of the series "Vanishing Tribes"

by the photographer Selvaprakash. Documented vendors who sell merchandise

The stereotyping notions which were built by the early colonial photographs and postcards during the early 1900s still remain beneath, The Independent India. It surfaces from time to time as a hangover. The early postcards reflected how Indians were often stereotyped based on ethnicity, gender, religion, or caste. Stereotyping in popular culture removes the identity of the individual and it becomes a generalised idea. But it also has a language in which we see that the detailing has been subtracted to make it look simple for mass understanding. The simplicity of this abstraction, which gives a totally different perspective without the claim of authentication, but in the process, it becomes a stereotypical thought. The conflict and contradiction of this language make it an interesting debate.

This language that began as a documentation practice, converted into popular culture in the times to come. It has also transformed and evolved from the first reference to ‘now’, in which the image changes its origin and becomes a separate identity not relating to the original thought. It is interesting to superimpose the origin and the now but then the thought occurs, was there an origin to begin with?

From the postcard collection of Martin Henry, Designed by Anchita Kaul

By Suresh Jayaram

The relationship between City and Cantonment was strange. It was neither one of friendship nor enmity. The English were not very interested in matters relating to the city. They managed to obtain the ‘ayahs’ ‘grooms’ ‘butler’ and ‘clerks’ they needed in the cantonment itself. Enough revenues were generated there to maintain their territories. We must admit that they kept their area clean and beautiful. Broad streets lined with trees, the large compounds of the military and civil officers, colourful gardens around each home, English women pushing children in prams: we must admit that in addition to the strange appearance of the foreign environment, Cantonment was also beautiful. The spaciousness, wealth of colour, peace, restfulness and beauty: none of this belonged to us, it was produced by the unconscious, alignment labour of our people for the foreigners. If we could forget this, we might enjoy it, but not even a moment’s interaction with the english allowed you to forget that fact. Even the most ordinary Englishmen had the superior air of the British empire.

A.N. Murthy Rao, ‘Bengaluru’, Samagra Lalitha Prabandhagalu, 1999

Postcards were introduced in India in the late 19th century (1879), with the insignia of Queen Victoria, it was priced at a quarter anna and was called the "East India PostCard." In the early decades of the 20th century, postcards were at the height of their popularity and were an innovative and affordable form of communicating. The proliferation of printing was an important factor that popularised this mass produced product that circulated in and outside India and established an image of colonial India. It has been estimated that in Britain alone approximately six billion postcards passed through the British postal system between 1902 and 1910.

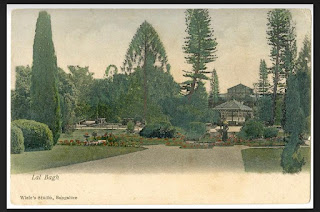

The postcards from Bangalore can be seen through the colonial lens of anthropology and the desire to connect with family and friends back home with images that capture a slice of the city, people, landscape, urban cityscape, colonial buildings and its famous gardens.The Postcards from India in general and specifically from Bangalore are often seen as nostalgic colonial momentos brought from old book shops, antique markets and specialised dealers who have amassed collections, and are sold to collectors with interest in colonial visual history and representation. They are not so much ‘a window into the past’, but a set of discursive coordinates that articulated the social and cultural geography of the city and its inhabitants, for a global and predominantly European audience.

Just like master

With reference to the exhibition at London's SOAS university (2018) by Stephan Putnam Huges and Emily Rose Stevenson, the curators categorised the postcards into Picturesque images of India, racial stereotypes, urbanization and daily life under the British rule. The most popular depictions were historical architecture and colonial buildings, and vignettes from everyday reality from the privileged colonial lives and quaint street scenes.The contentious relationship between the Memsahibs, sahibs who served their life of leisure and employed the “natives,” the locals, as Maalis, Dhobhis, Pankhavalas, bearers, ayahas, cooks and domestic helpers. A certain series that looks like a retake on the natives depicting them in the poses of the masters in studio settings look humorous at first sight but are racist narratives of the colonial establishment who believed that the local depiction of "British anxieties'' and "insecurities"about what the "servant" would do when the "master" was not around.

Bangalore Hunt Postcards

The satirical "Bangalore hunt" referred to the hound hunts of the British; this postcard might be a staged depiction of women picking head lice from each other sitting in row. These postcards reinforced colonial depictions of stereotyping India and Indians. As we decolonize these postcards, the visual culture of representation from the colonial experience and postcolonial critique has been the subject of sustained critical analysis. These postcards deal with cross-cultural encounters of representation of images, spaces and built structures, on the visual cultures of British India. Most of them continued the aesthetic and politics of representations of colonial photography by British photographers whose depictions are problematic and raise several questions about the Colonial representation of "other" in India through these ubiquitous postcards.